Writing fiction is simply telling a story. Humans have been storytelling for millennia, from recounting tales while sitting around a fire to modern day blogging and stories told on social media.

The history of medicine is rife with outstanding storytellers, including W Somerset Maugham, Arthur Conan Doyle, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Anton Chekhov and William Carlos Williams, along with more contemporary authors such as Robin Cook, Michael Crichton, Abraham Verghese, Khaled Hosseini and others.

Chekhov captured the appeal of writing when he wrote: “Medicine is my lawful wife and literature my mistress; when I get tired of one, I spend the night with the other.”

Physicians are trained to be professional storytellers from our first days as medical students when we present a patient to a staff physician on rounds or write a patient summary for the chart or for a referral. We are privileged to be present when people are literally or figuratively undressed during momentous occasions such as childbirth, illness and death. We are taught empathy, while retaining objectivity when observing life’s great dramas. These storytelling skills serve physicians who write fiction well.

Science Writing Versus Fiction

Accuracy and clarity are two virtues of medical writing that are drilled into us, whether it is describing a patient’s illness or reporting the results of a study. Such reporting contains elements of novel writing. For example, charting a patient’s history begins with a chief complaint, which is like the opening paragraphs; history, physical exam and lab data are like the middle of a novel; and diagnosis and treatment are the final chapters.

A scientific article is generally more rigidly divided into an introduction, methods, results and discussion in which the author describes what he is about to present, states the tools used, relates the results and recapitulates the entire experience. The physician/science writer remains totally impersonal, while the fiction writer can become intensely involved in the story through his past experiences.

Fiction writing, in contrast to science writing, involves using an eyedropper to dispense a fact here, another there, and a third 10 pages later, taking the reader through unexpected twists and turns to reach the final outcome. It is an elaborate lie used to tell the truth to explain and explore life.

Fiction allows for the creative freedom to invent your own universe, to imagine a world without boundaries, to conceive characters you love and make into heroes, or characters you hate that you can kill if you so choose. It is exhilarating and a world apart from writing tightly regulated science.

Every novel has a purpose or premise, such as ‘ruthless ambition destroys itself’, and is comprised of three important elements that I call the 3Cs: character, conflict and conclusion. Each C must be fully developed and instead of scientific clarity, fiction authors strive for suspense; instead of medical accuracy, we seek drama; and instead of resolution, we pursue conflict until the end.

Another, more practical, distinction is that the fiction author retains copyright ownership, in contrast to publishing in a medical journal or textbook where the author relinquishes the copyright to the publisher.

A novel can be any length, from hundreds of thousands of words such as Tolstoy’s War and Peace to as short as six: ‘For sale; baby shoes; never worn,’ which has been attributed to Ernest Hemingway.

Ninety per cent of fiction writing is revision. When Oscar Wilde was asked how he spent his morning, he answered: “I spent it revising a poem.”

“What changes did you make?”

“I took out a comma.”

“What did you do in the afternoon?”

“I put it back.”

Good fiction emphasises ‘showing’ rather than ‘telling’; adverbs such as quickly, angrily and briefly are banished, replaced by active descriptions depicting each state or condition. The active voice supplants the passive, and point of view must be consistent. However, all rules are made to be broken as long as the transgression propels the story forward.

First Attempt at Writing a Novel

My first attempt at novel writing began long before computers were commonplace and I had not yet learned to type. At work I had a secretary and dictated everything I needed to be written. After reading a bestselling medical thriller, I decided to try and write one. I began dictating my novel, bringing the tapes home to my wife for transcription. As she typed, she rearranged sentences and substituted words and gradually became my coauthor.

Therein lay the danger. We viewed scenes and characters differently. She would advise: “No woman would say that while making love,” and I would retort: “No man is going to act like that in a fight.” We held countless conversations over dinner. My wife called them discussions; I called them arguments. She liked them; I didn’t.

The only way we could agree on a scene or a character was to compromise, a fatal tactic that blunted the sharp edges of the story. Scenes and characters had to be negotiated to please us both and we lost the vibrancy of the tale. In the end, we relegated this first team effort to a drawer where 110,000 words slumber peacefully, perhaps awaiting resuscitation during the throes of a long, cold Indiana winter while we are sitting alongside a blazing, toasty fire.

The Black Widows

The premise of my first completed novel The Black Widows, published in 2011, is based on the concept that evil begets its own downfall (Figure 1).1 Two elderly widows control a worldwide terrorist operation that seeks to overthrow Western democracy. Foreword Reviews chose it as a Book of the Year finalist. The prologue of the novel sets forth several precepts emphasised above.

“Wahad, code name for ‘the first’, slipped into the building, past the guard… The first kill was always the toughest… Wahad slid a finger through the trigger guard, aimed and slowly squeezed… and began the surgical procedure. Number one was completed. Only 999 to go.”

The reader doesn’t know who Wahad is, and I carefully avoided pronouns to identify Wahad’s sex. ‘The first kill’ – of whom and why? Followed by ‘a surgical procedure’ – what? Why? And ‘999 to go’ – oh my God!

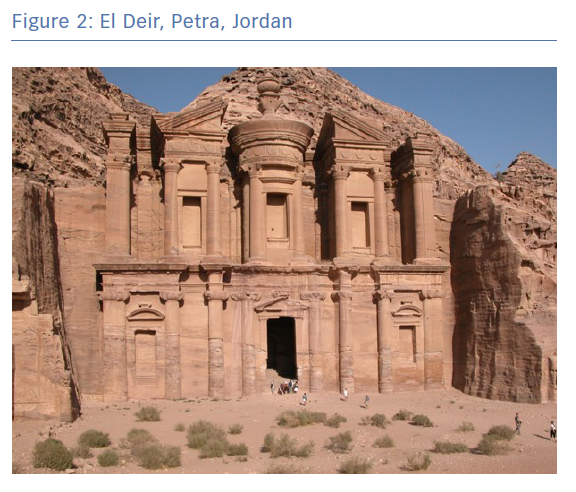

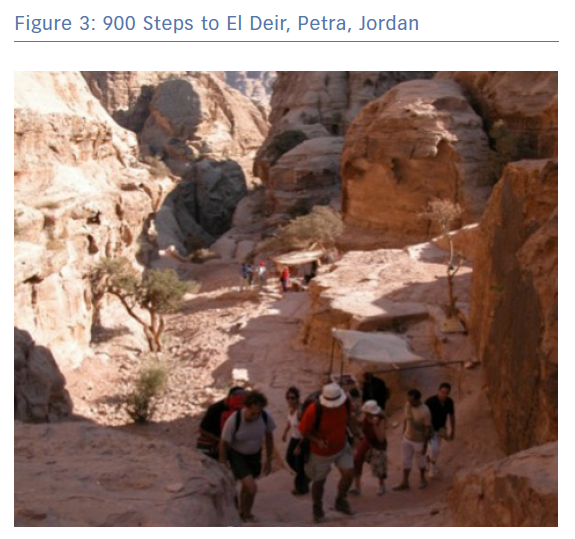

A rewarding experience for an author is to weave one’s own personal experiences into the novel. I had toured Petra and Jordan around the time I was writing The Black Widows, so I ended the novel with the hero chasing the leader of the terrorists to Petra. The terrorists have used El Deir to create a hidden laboratory in which they fashioned weapons of mass destruction (Figure 2). The leader of the Black Widows has captured the heroine and is planning to stone her to death on the plateau in front of the building. Petra has 900 steps (Figure 3), leading to El Deir. Here is an excerpt from one of the final chapters:

“A nine-hundred-step run is agonizing… the stairs were uneven and twisted in, out, and around the mountainside, and the sun was hot… my calves bunched into knots, my breath was raspy and rapid, and my heart rate too fast to count. My body told me to stop and rest while my head said, Keep going—she may still be alive.

“I won’t let her die today!

“Finally I reached the last step, wheezing like an asthmatic. It opened onto the plateau in front of El Deir. A circle of people stood around a white robed statue, buried to the shoulders in a hole. The sheet was tied with a string at the top like a sack of laundry…

“He hurled the rock, hitting its target. A red stain spread across the top of the sheet… she… lost consciousness.”

Ripples in Opperman’s Pond

I used my second novel Ripples in Opperman’s Pond to explore genotype/phenotype mismatch by having identical twin brothers – both cardiologists – exhibit totally different personalities (Figure 4).2 I also tried to create an opening sentence that readers would remember, as they remember “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” from A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, or “Call me Ishmael” from Moby Dick by Herman Melville. In Ripples, one twin says of the other, “We were identical, Dorian and I, but not at all alike.”

The premise, that ruthless ambition breeds self-destruction, stems from two trials at which I testified as an expert witness. Reggie Lewis (b. 1965, d. 1993), a Boston Celtics basketball star, suffered sudden cardiac death while being evaluated for syncope by a cardiologist at a Boston hospital. His wife sued the cardiologist for malpractice and I was asked to testify (successfully) in his defence. In the second trial, I was a plaintiff expert witness testifying against Merck Pharmaceuticals in 2006, alleging their drug Vioxx (rofecoxib) caused a heart attack in a patient. The jury awarded $51 million to the plaintiff.

Here is an excerpt from the first chapter of Ripples:

”Randy hit his patented fall-away jumper as the game-ending buzzer sounded… guaranteeing the Pacers a play-off berth. Not planned was Randy’s mid-air collision with the Boston guard… Unbalanced, Randy landed on a bowed-out ankle, fragile ligaments suddenly supporting 225 crashing pounds. Randy’s scream drowned the papery whisper of the ball’s swish as he fell.”

One brother’s newly discovered anti-inflammatory drug, Redex, is used to treat Randy. Predictably, Randy suffers sudden cardiac death as the novel unfolds and his twin is sued for malpractice.

Not Just a Game

The premise of my third novel Not Just a Game is that good overcomes evil (Figure 5).3 I wrote it to focus attention on the growing menace of far-right extremism, the rise in anti-Semitism, along with the resurgence of Nazism.

I created three generations of a single family from which the father, son and granddaughter each participate in an important summer Olympics: the father in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin hosted by Adolf Hitler; the son in the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich during which the Black September Palestinian terrorist group murdered 11 Israeli athletes; and the granddaughter in the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro when, in this fictional account, the Nazi Fourth Reich raises its virulent head to stage a re-enactment of Kristallnacht. The original Kristallnacht took place in Nazi Germany, 9–10 November 1938, and was the beginning of the Holocaust.

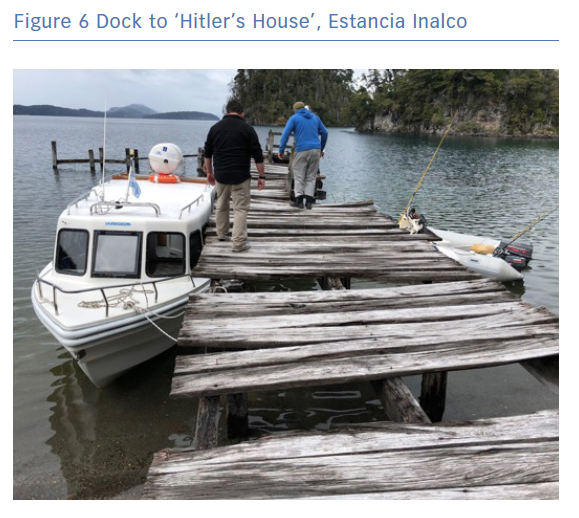

The story draws from the conspiracy theory that Hitler survived World War II and fled to South America where he is said to have lived in a house in La Angostura, Argentina, which I visited last year (Figures 6 and 7). I have imagined him there, sowing the seeds for the Fourth Reich. The granddaughter in my novel, Kirsten, becomes the last hope to subdue and transform the uprising through a series of interconnected events. She speaks to the citizens of Rio on national television after the first night of riots to try and prevent an even more violent second night. The teleprompter has just quit and she is winging it.

“She panicked. What should I do? Words spoken more than two thousand years ago came to her, reassured and calmed her.

“A famous rabbi named Hillel once said, ‘If I am not for myself, who is for me? And being for my own self, what am I? And if not now, when?’

“So, I have to help, now, in any way I can, and try to make you realize what you are doing and the horrible consequences of your actions.

“All of this is as new to me as it is to you. I didn’t ask for the role… I must try to prevent a second night of Kristallnacht.”’

A Failure to Warn

In A Failure to Warn (tentative title), I used for inspiration my 9-year battle as a plaintiff expert witness against TASER International.4 I argued in multiple sudden death lawsuits that their weapon could cause cardiac arrest.

For the novel, I fabricated the story of a family wiped out by an electronic control weapon manufactured by the fictitious Electric Gun Company. The last survivor beseeches her lawyer brother:

“Just promise me you’ll go after the people responsible for killing my men and bring them to justice. If I know you’ll do that, I’ll die and can rest in peace.”

Damn the Naysayers

I wrote my memoir Damn the Naysayers to capture for myself, my family, and my friends, personal highlights over the past 80 years that have illuminated and affected my life (Figure 8).5 I am indebted to my friend and colleague Eugene Braunwald for writing the foreword.

Transitioning from writing fiction to writing a memoir is an interesting challenge because of the tricks one’s memory plays, particularly recalling events that happened a long time ago (though sometimes incidents 50 years old remain more vivid than last night’s dinner). Just as my personal memories influenced my fiction, all memoirs inevitably contain some fiction. But a true memoir must be told from the author’s memory, however flawed, and from the subjective recollection of events, shaded by the author’s personal point of view, by who he is and the facts as he remembers them.

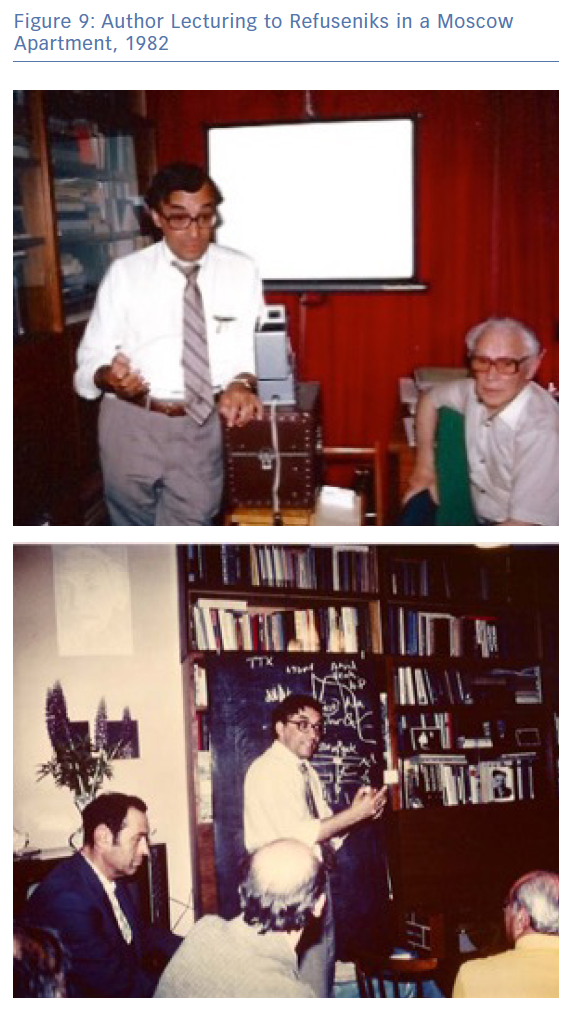

I began the memoir with one of the most terrifying yet rewarding events in my entire life: lecturing to refuseniks in Moscow at the height of the Cold War (Figure 9). The Saturday Evening Post published that first chapter in its entirety (Figure 10).

“Are you Douglas Zipes, the heart specialist from Indiana?” the deep voice over the phone asked. “I am a refusenik. We are in a jail without bars,” he said.

“I’m sorry for that,” I said. “But why are you calling me?”

“How brave are you?” he asked. “We need someone with courage. Two years ago, we started the Sunday Seminars. When a major scientific meeting was going to be held in Moscow, one of us would invite a visiting scientist to give us a private lecture – on Sundays. One evening during the lecture, the KGB burst in. The owner of the apartment was arrested and exiled for 3 years to Kazakhstan. That ended the Sunday Seminars… you could be trusted.”

“Trusted? To do what?” I asked, my voice tremulous.

“To be our first scientist to restart our Sunday Seminars.”

Conclusion

I emphasised recently that life’s journey is more important than the finish.6 This is particularly applicable to my late-blooming career in fiction. My transition from cardiologist to novelist has been like travelling from Who’s Who to Who’s He?

I admire the successes of the writers featured above, much as an intern would admire the skills of staff physicians. But I’m still young, and if I work hard at my writing, who knows what I can accomplish in the next 80 years. With a bit of luck, maybe I will join that list.