AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and poses a significant public health challenge.1 In cases of AF, if sinus rhythm does not spontaneously return, cardioversion may be needed to alleviate symptoms and to improve cardiac performance.2 This may be performed by pharmacological methods, i.e. the administration of antiarrhythmic drugs, which is the preferred strategy in recent-onset AF, or by direct current electrical cardioversion, which is preferred in prolonged AF.2 The latter is more effective than pharmacological cardioversion, especially in persistent AF, although it requires anaesthesia and well-trained staff.2 A recent European survey found that the use of cardioversion in patients with AF is increasing.3

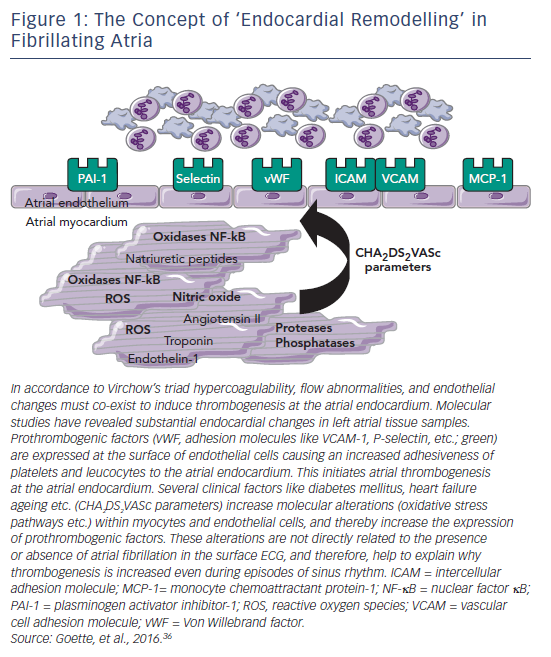

However, cardioversion itself carries an inherent risk of thromboembolic complications in AF,4 due to the possible embolisation of pre-existing thrombus from the atrial appendage.5 In this setting, the process of thrombogenic endocardial remodelling appears to be of importance. In addition, the process of cardioversion may promote new thrombus formation due to transient atrial dysfunction (‘stunning’), which is related to the duration of AF rather than the mode of cardioversion.6,7 In particular, comorbidities such as heart failure, hypertension or ageing induce a thrombogenic endocardial remodelling that persists even after restoration of sinus rhythm (see Figure 1).8 This increased risk has led to recommendations for the use of anticoagulation before and after cardioversion. Without adequate anticoagulation, the risk of thromboembolism associated with cardioversion is 5–7 %.9 The use of prophylactic anticoagulation can reduce this risk to <1 %.10–12 Historically, the standard therapy for AF has been warfarin, but in recent years, the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban and rivaroxaban have been approved for the prevention of stroke in patients with AF, after demonstrating non-inferiority to warfarin in clinical trials.13–16 Furthermore, clinical data indicate that patients receiving DOAC therapy as an alternative to warfarin can be safely cardioverted.17–19 In this article we aim to discuss the guidelines for the use of anticoagulation in cardioversion and review the clinical evidence in favour of the use of DOACs in this indication.

Guidelines and Recommendations on the Use of Anticoagulants in Cardioversion

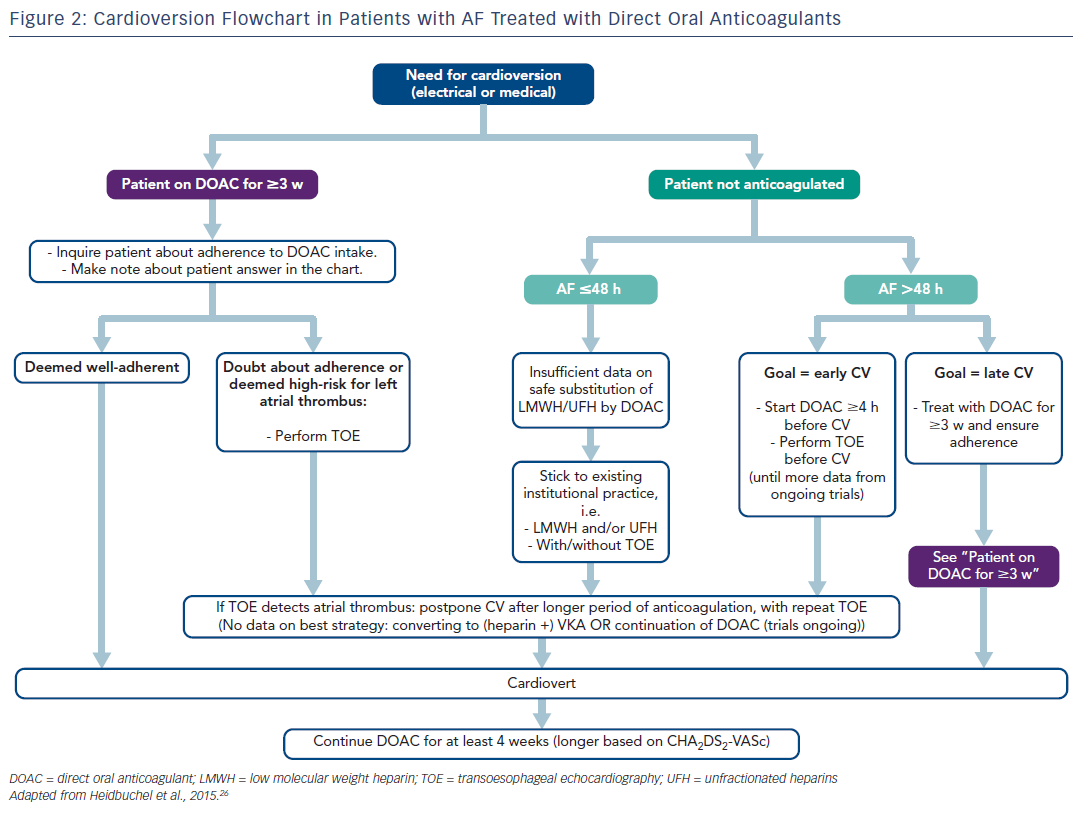

For patients undergoing cardioversion it is important to consider duration of AF and prior anticoagulation.20 The 2016 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on cardioversion state that patients who have been in AF for longer than 48 hours should start OAC therapy at least 3 weeks before cardioversion and continue for 4 weeks afterwards (in those without a need for long-term anticoagulation). If transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) is available and acceptable to the patient, it may be used to exclude the majority of left atrial thrombi (which would preclude the procedure), allowing immediate cardioversion shortly after the start of anticoagulation, but without precluding the need for ≥4 weeks treatment afterwards. OAC therapy should be continued indefinitely in patients at increased risk of stroke. When cardioverting AF of ≤48 hours in an anticoagulation-näive patient, the guidelines do not formally advise pre-treatment with OAC and/or TOE, but advise clinicians to follow institutional practice of administering heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) with/ without TOE before cardioversion.

However, a large observational study has suggested that even for patients with an AF lasting ≤48 hours, there may be a durationdependent risk for thromboembolism.21 Current guidelines recommend deferral of cardioversion and vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy for 3 weeks following detection of a left atrial or left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with AF despite long-term anticoagulant treatment. The use of TOE before cardioversion is controversial: while some data exist to support its use,22,23 it has been argued that current evidence is insufficient to justify its cost. In addition, TOE may fail to detect small thrombi, TOE examination is labour intensive, and small medical centres may lack the necessary expertise to detect thrombi.24,25

The European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide26 makes the following recommendations about the use of DOACs in cardioversion (see Figure 2). First, when cardioverting a patient with AF being treated for ≥3 weeks with DOACs, it is important to ask about adherence. If in doubt, TOE should be performed prior to cardioversion. When cardioverting AF of >48 hours in a patient not on DOACs, a strategy with at least a single DOAC dose ≥4 hours before cardioversion is safe and effective, provided that a TOE is performed prior to cardioversion. The alternative is at least 3 weeks of well-adherent DOAC therapy before scheduled cardioversion. The same scenario applies when the exact duration of AF cannot be established with certainty, which is often the case. When cardioverting AF that definitely lasts ≤48 hours in an anticoagulation-näive patient, adherence to institutional practice with heparin/LMWH with/without TOE is advised. Most institutions will opt to administer any anticoagulation with LMWH or unfractionated heparin before cardioversion in most of these patients. Given the increasing evidence from prospective trials such as X-VERT (Explore the Efficacy and Safety of Once-daily Oral Rivaroxaban for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Subjects With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Scheduled for Cardioversion; NCT01674647) and ENSURE-AF (Edoxaban vs Warfarin in Subjects Undergoing Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation; NCT02072434), substitution of the pre-cardioversion administration of LMWH by DOAC seems defendable.

Patients with documented left atrial appendage thrombus should not undergo cardioversion. Rigorously followed-up international normalised ratio (INR) monitoring under VKA therapy until resolution of the thrombus is recommended (with heparin bridging if necessary), as long as trial data have not confirmed an equally effective and safe course with DOACs in this scenario. In addition, patients must be educated about the importance of treatment adherence and persistence, as missing DOAC doses leads to suboptimal anticoagulation and an increased risk of thromboembolic events.

In February 2017, the American Heart Association released a scientific statement regarding the management of patients taking DOACs in the acute care and periprocedural setting.27 The recommendations for patients undergoing cardioversion were similar to the European guidelines. Patients should be anticoagulated for ≥3 weeks before elective cardioversion. If not, then a TOE should be performed to exclude the presence of left atrial appendage or left atrial thrombus. If a patient’s adherence to therapy is suboptimal (at least two missed doses) or in question, then a TOE should be considered. If a patient is found to have left atrial appendage or left atrial thrombus, then an alternate anticoagulant should be considered, with special attention to consistent anticoagulant use during the transition.27

Practical Problems Associated with Warfarin Anticoagulation

Limitations associated with the use of warfarin are well documented and include inter- and intra-individual variations in INR values, drug–drug interactions and the requirement for frequent INR testing. The use of warfarin can also delay cardioversion due to the timeconsuming nature of warfarin initiation and difficulties in achieving a target INR between 2 and 3 before cardioversion, and maintaining it stably within that range.25 A retrospective study of 288 consecutive patients with AF scheduled for elective cardioversion found that the median treatment duration prior to cardioversion with warfarin was 12 weeks, exceeding by far the recommended 3 weeks.28 Because warfarin takes several days to have a therapeutic effect, patients presenting with acute AF are typically treated with intravenous heparin or subcutaneous LMWH while they are awaiting stable INR values and cardioversion. In a recent study of 346 patients taking VKA prior to elective cardioversion, 55.2 % had a subtherapeutic INR prior to cardioversion.29 These data highlight the need for better anticoagulation options in patients requiring cardioversion.

Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Patients Undergoing Cardioversion

The pharmacological characteristics of the DOACs make them well suited to use in the setting of cardioversion. Their rapid onset of action (2–4 hours), short half-life and predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics offer the potential benefit of their initiation in the outpatient setting and can potentially reduce the rate of hospitalisation and associated costs.

Post-hoc analyses of data from the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY; 1,983 cardioversions in 1,270 patients),17 Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE; 743 cardioversions in 540 patients),18 Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKETAF; 460 cardioversions in 321 patients)30 and Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48; 632 cardioversions in 365 patients)31 trials have shown that thromboembolic and major bleeding events following cardioversion were infrequent and their incidence was not statistically different to those seen with VKAs when the precardioversion anticoagulation time period is long (i.e. patients on a chronic maintenance dose of anticoagulation). However, these were post-hoc, nonrandomised observations.

The safety of dabigatran in patients undergoing electrical cardioversion has also been demonstrated in two other retrospective studies. The first (n=525) showed that the average time for treatment before cardioversion was significantly lower for dabigatran (25 days) versus warfarin (35 days; p<0.01).32 The second study comprised 631 patients, including 570 who were näive to OAC therapy when dabigatran was initiated and a warfarin control group (n=166). The median time from initiation of dabigatran to first cardioversion was 32 days versus 74 days with warfarin. In addition, treatment for 1 month with dabigatran before cardioversion was associated with a low incidence of thromboembolism (0.53 % over 30-day follow-up), even in anticoagulant-näive patients.33

The use of DOACs for cardioversion appears to be cost effective and increases the efficiency of cardioversion services. A retrospective study examined the impact of dabigatran, as an alternative to warfarin, on the efficiency of an outpatient electrical cardioversion service.34 A total of 242 procedures performed on 193 patients over a 36-month period were analysed. Patients who received dabigatran had significantly lower rates of rescheduling compared with those who received warfarin (9.7 % versus 34.4 %; p<0.001). The length of time between initial assessment and cardioversion was 22 days shorter for those who took dabigatran than warfarin (p=0.0015).34

A recent meta-analysis of the RE-LY, ROCKET-AF, ARISTOTLE, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48, and X-VeRT trials concluded that the short-term incidences of thromboembolic and major haemorrhagic events after cardioversion were low with DOACs and similar to those observed on dose-adjusted VKA therapy.35

Prospective Trials Investigating Direct Oral Coagulants in Patients Undergoing Cardioversion

In the X-VeRT study, a prospective, randomised controlled trial in patients with AF undergoing elective cardioversion, rivaroxaban was compared with VKAs.19 Patients were randomised to a once-daily dose of rivaroxaban 20 mg orally (15 mg once daily in patients with creatinine clearance of 30–49 mL/min) or warfarin/another VKA at the investigator’s discretion. The target INR was 2.5 (range 2.0–3.0). Investigators had the option to use a parenteral anticoagulant drug in addition to VKA therapy, especially prior to cardioversion, until the target INR was obtained. In the early cardioversion strategy group, rivaroxaban or a VKA was given 1–5 days before intended cardioversion and continued for 6 weeks following cardioversion. In the delayed cardioversion strategy group, patients were given either a VKA or rivaroxaban for ≥3 weeks and ≤8 weeks before cardioversion. The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of stroke, transient ischaemic attack, peripheral embolism, MI and cardiovascular death. The primary safety outcome was major bleeding. Note that the trial was not powered to show significance on ischaemic or bleeding endpoints as this would have required the enrolment of around 30,000 patients. The incidence of both endpoints was comparable between rivaroxaban and VKA groups, with a numerical trend for lower ischaemic and bleeding outcomes in the rivaroxaban-treated patients. In addition, rivaroxaban was associated with a significantly shorter time to cardioversion compared with VKAs. Of the entire cohort, 77.6 % underwent cardioversion after anticoagulation within the target time range, primarily due to failure to achieve adequate anticoagulation (rivaroxaban: 1 patient, VKA: 95 patients). Among patients assigned to delayed cardioversion, 77 % of those in the rivaroxaban group and 36 % of those who received VKA underwent cardioversion within the target time range (p<0.001).19 It should be noted, however, that in this study almost 60 % of the patients with rivaroxaban treatment underwent TOE and patients with left atrial thrombus were excluded.

The largest prospective clinical trial on cardioversion of persistent AF so far, the ENSURE-AF trial compared the use of edoxaban with enoxaparin–warfarin in patients undergoing electrical cardioversion.36 Patients (n=2,199) were stratified according to cardioversion approach (TOE or non-TOE) and randomly assigned to receive edoxaban (n=1,095) or enoxaparin-warfarin (n=1,104).

By contrast to the X-VeRT trial, the optimised strategy of enoxaparin bridging was selected for the comparator arm to reduce time to achieve the INR and to cover transient suboptimal anticoagulation periods with warfarin alone.36 In the TOE stratum, the cardioversion procedure had to be performed within a maximum of 3 days from randomisation. Patients in the enoxaparin–warfarin group with INR <2.0 received a minimum of one dose each of enoxaparin and warfarin before cardioversion, and these drugs were continued until INR >2.0 was obtained. Measurements were made once every 2–3 days until the therapeutic range was achieved. After achieving therapeutic range, patients discontinued enoxaparin and continue warfarin until end of treatment (day 28 after the procedure). Patients in the enoxaparin–warfarin group with INR >2 at the time of randomisation were treated with warfarin alone. The dose was adjusted to achieve and maintain the therapeutic INR of 2–3. Subsequently, patients attended planned study visits, but were given ad-hoc INR checks if considered necessary by the investigator. Patients in the edoxaban group had to start treatment at least 2 hours before cardioversion. The next dose of edoxaban was taken the day after cardioversion and then continued daily until day 28 post-cardioversion. The primary efficacy endpoint in ENSURE-AF was the composite of stroke, systemic embolic event, MI and cardiovascular mortality, and showed a similar incidence for edoxaban and enoxaparin–warfarin (0.5 % versus 1.0 %, respectively; odds ratio [OR], 0.46; 95 % CI [0.12–1.43]). The main difference between the treatment groups was in cardiovascular mortality, with one event in the edoxaban group and five events in the enoxaparin–warfarin group (0.1 % versus 0.5 %, respectively). Rates of major bleeding were low for patients receiving edoxaban and comparable with those randomised to enoxaparin–warfarin over 2 months of follow-up (0.3 % versus 0.5 %, respectively; OR: 0.61; 95 % CI [0.09–0.13]). No intracranial bleedings were reported in the study in either of the treatment groups. No fatal bleeding was reported in the edoxaban group versus one patient in the enoxaparin–warfarin group. The results were independent of whether cardioversion was guided by TOE, which occurred in about half of patients in each of the edoxaban and enoxaparin groups.36 Unlike the X-VeRT trial, the enoxaparin lead-in resulted in better VKA treatment, allowing more patients in the VKA arm to achieve the required INR and undergo cardioversion. However, due to the low incidence of ischaemic events during cardioversion, ENSURE AF and X-VeRT trials were not statistically powered to demonstrate significance.

A third prospective cardioversion trial, EMANATE (apixaban, NCT02100228) will soon report on the use of DOACs in AF patients.

Other prospective randomised clinical trials are underway in patients scheduled for cardioversion, but in whom the TOE finding of left atrial appendage thrombus precludes cardioversion: RE-LATED-AF (dabigatran, NCT02256683) and X-TRA (rivaroxaban, NCT01839357). In the X-TRA study, resolved or reduced thrombus (as assessed centrally by blinded, independent adjudicators) was evident in 60.4 % of the modified intention-to-treat patient population, including two patients with two thrombi resolved in each case, demonstrating the potential of rivaroxaban in this setting.37

Practical Advantages Offered by Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Cardioversion

The rapid onset of action of DOACs offers the potential benefit of their initiation in the outpatient setting and can potentially reduce the rate of hospitalisation and associated costs. Based on the results of the ENSURE-AF study, a newly diagnosed and non-anticoagulated patient with AF could be started on edoxaban and the cardioversion procedure scheduled as early as 2 hours after the start of treatment with a TOE-guided approach, or elective cardioversion could be performed 3 weeks later without TOE, eliminating the risk to reschedule the cardioversion due to inadequate INR.36 The use of DOACs assures that cardioversions can occur at the planned time, which is advantageous as it prevents rescheduling. An important element to stress to the patient, however, is the need for perfect adherence to medication intake (once daily in the case of edoxaban).

Conclusion

With the increased use of DOACs in routine clinical practice, several practical issues have emerged, including considerations for cardioversion. Cardioversion restores sinus rhythm in AF and can improve cardiac symptoms, but is associated with increased thromboembolic risks. While warfarin can decrease these risks, its use is associated with delayed procedures due to its slow onset of action. By contrast, DOACs act rapidly, have a short half-life and predictable pharmacokinetics. Two randomised clinical studies, X-VERT and ENSURE-AF, have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban and edoxaban, respectively, in this setting. Compared with warfarin or other VKAs, both have been found to reduce the time between administration and cardioversion and may facilitate more predictability in planning cardioversions. Results from ongoing and future studies will add further data to inform optimal use of these agents.